Nature Photo Planner

The idea came years ago. It was too much then. Last summer I watched a video suggesting you could get ChatGPT to write small little programs by asking it to write something as a standalone html app using its canvas function. Since then, it has become a major project.

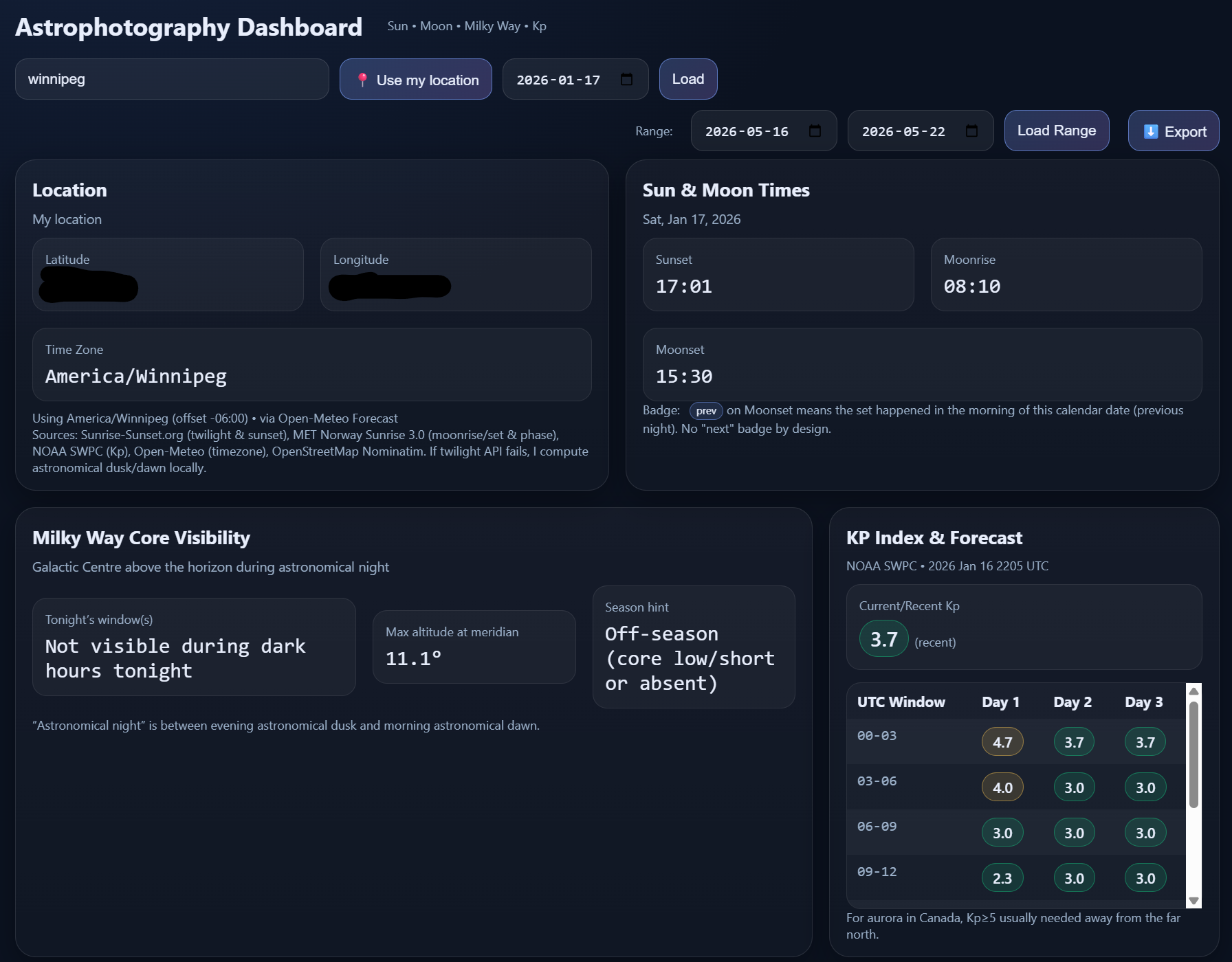

That was the first time my tools started to take shape in the form of software. The first one was this Astrophotography Dashboard idea I’d been cooking up for a while. I could enter where I was and pick a date range. It would fill a top section with that evening’s shooting conditions and then produce a chart showing key astrophotography planning information for those nights. It could even highlight the best nights and list the best five in a summary at the top. It went and fetched the information from other sites.

The original HTML app.

My “best night” chart.

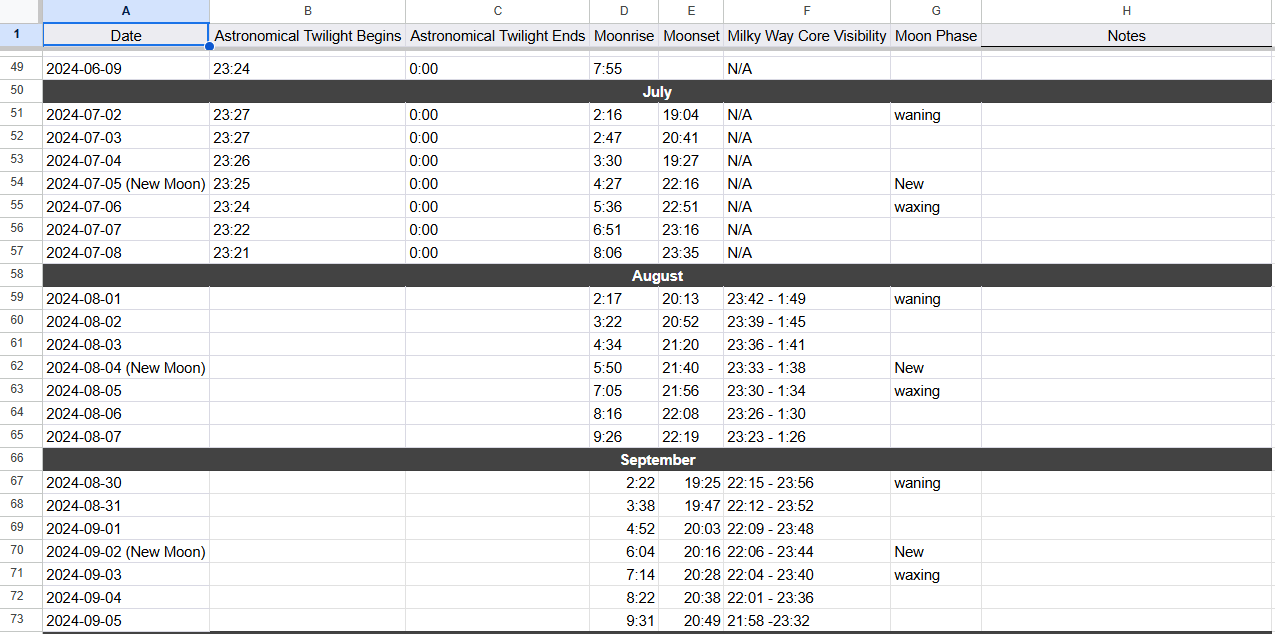

The dashboard was already pretty cool. It was exciting to have a tool like that. It was very easy to set a location and a date. Those were the important bits anyway. The colour coded table was already so much better than my alternative. I was using PhotoPills before. Like everybody else. But when trying to compare nights, or long term planning, the manually scrubbing through day by day using inputs buried layers deep. Then there was manually entering collected information into a spreadsheet. And that was only good for one location. Where and when the Milky Way core will be, and even its shape heavily depend on your longitude and more heavily, latitude. This most basic form of my tool was already solving real pain points.

Previous to my tools, my spreadsheet was limited to 7 nights per week because of the time it took to manually fill it out after scanning through data one night at a time.

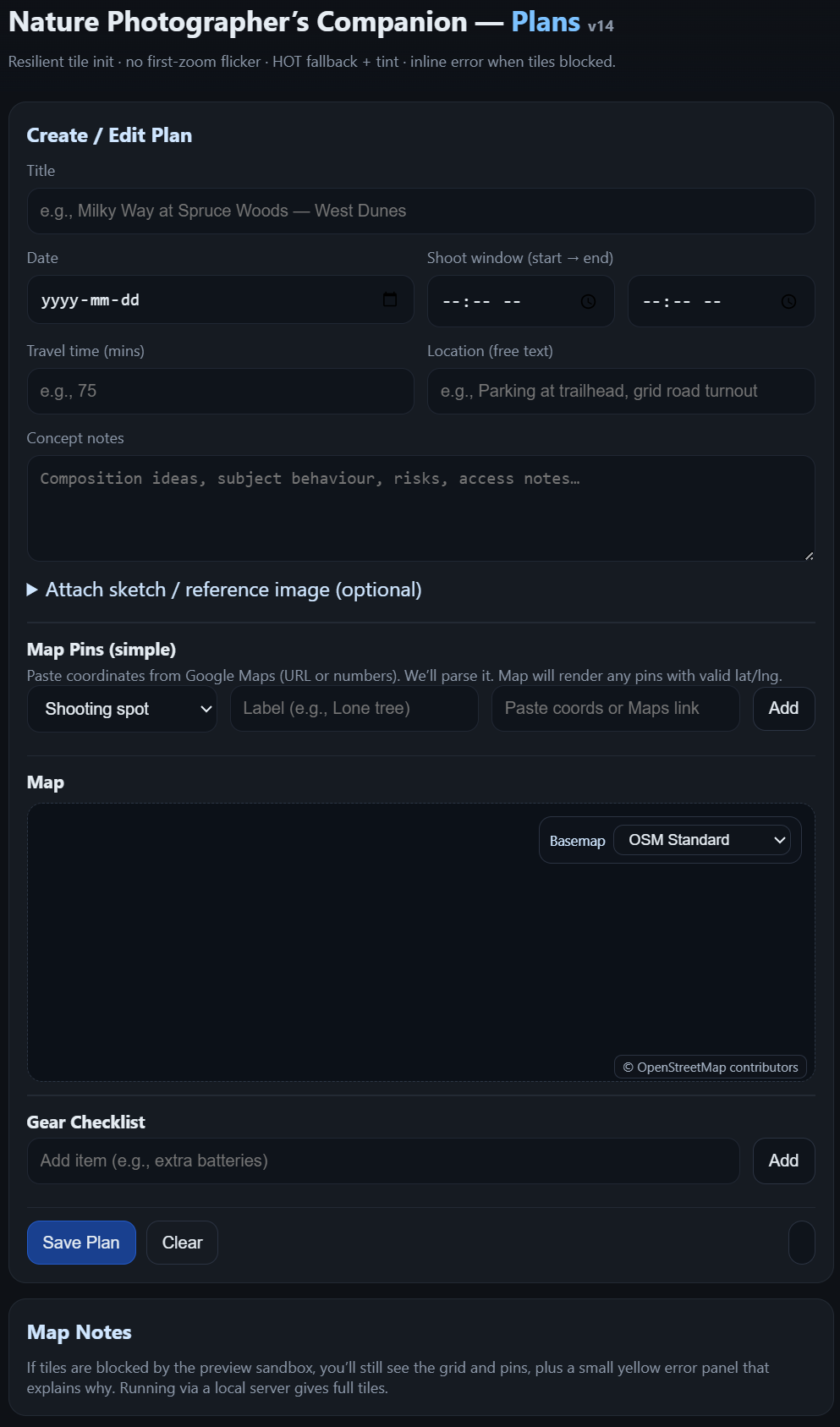

The next tool I made was like a little plan journal. I got it to work, sort of, then abandoned it. I knew there would be value in it, but not in this form. I could make plans with all kinds of contextual information. Editing, saving, and loading plans was really clumsy.

The HTML based planner was lacking in a lot of ways.

Planning is actually a critical part of landscape astrophotography. It’s a very technical process beyond pressing the shutter release with the correct settings. Your best photos don’t happen by accident.

Imagine trying to line up this composition in the middle of the night. Including finding the flower in the dark.

Often the plan can be to show up early to take a look around. That can work for some things. Maybe though that’s just your first trip, where you go to figure out if it will all work.

When I mentioned the Milky Way will be visible depending on time, date, and location, that’s because the sky changes with the seasons as we orbit the sun. During the Canadian summer, our nights face towards the centre of our galaxy, the Milky Way. When most people say the Milky Way, they are usually referring to the galactic core. The sky gets very busy in that direction and looks the most spectacular. During our winter nights, our view faces outwards, towards the edge of the galaxy and beyond. The core is not visible at all for months in the deep of winter. When it becomes visible, it's more east and drifts more to the west every night until eventually it doesn’t rise above the horizon again until the next spring.

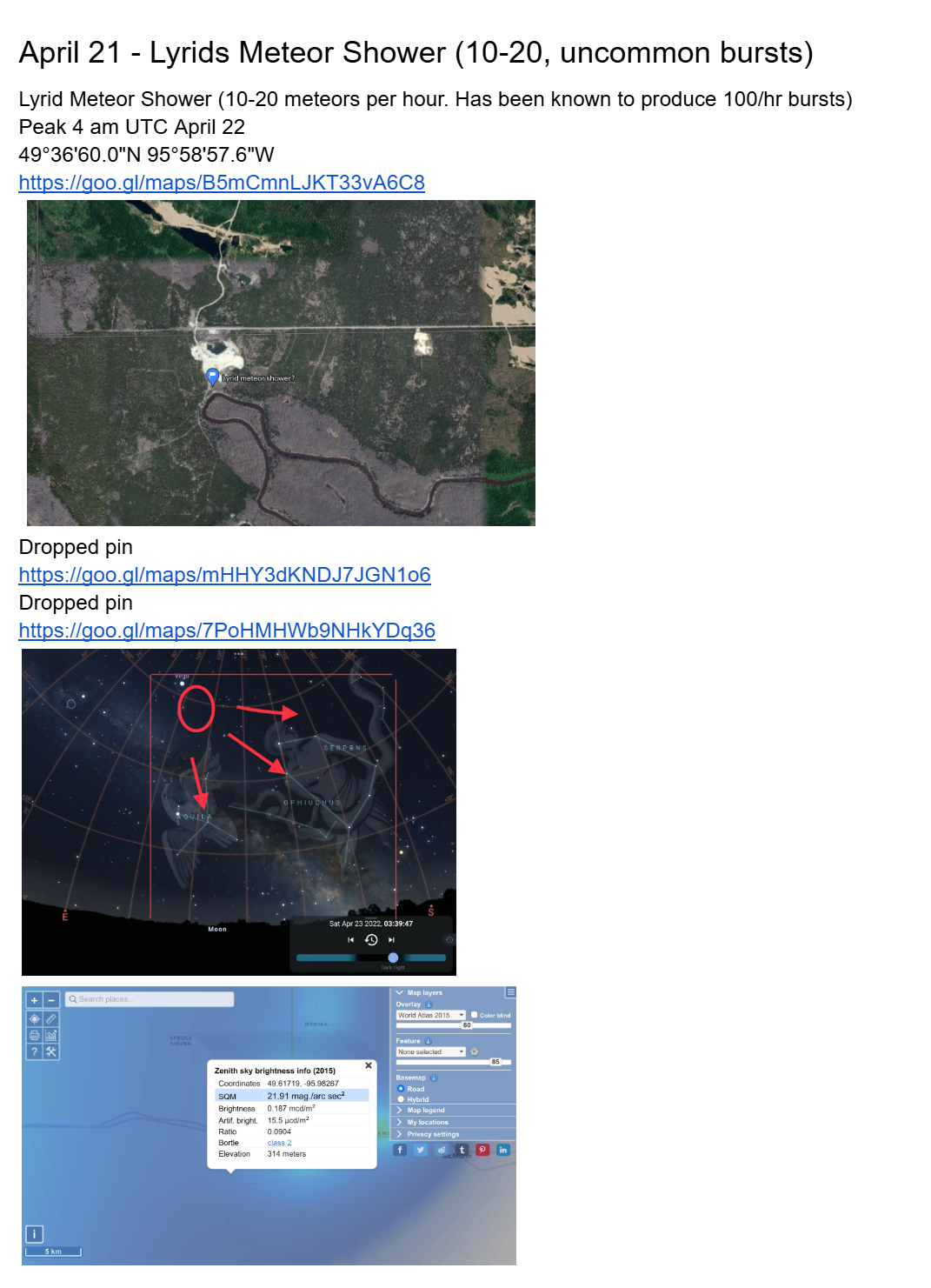

If you have a specific composition in mind, such as the Milky Way core rising through the mouth of Ouimet Canyon, you can’t just show up one night and hope for the best. It’s not likely to work just the way you wanted.

Once I have an idea in mind, and figure out if and then when the galactic core will align with my foreground, I write it down somewhere. That somewhere ended up being in a Google doc. So the new plans tool looked pretty good, but still missing something. Below is from my Google doc on the left, my new planner on the right.

Google Doc plan

Plan built through my app

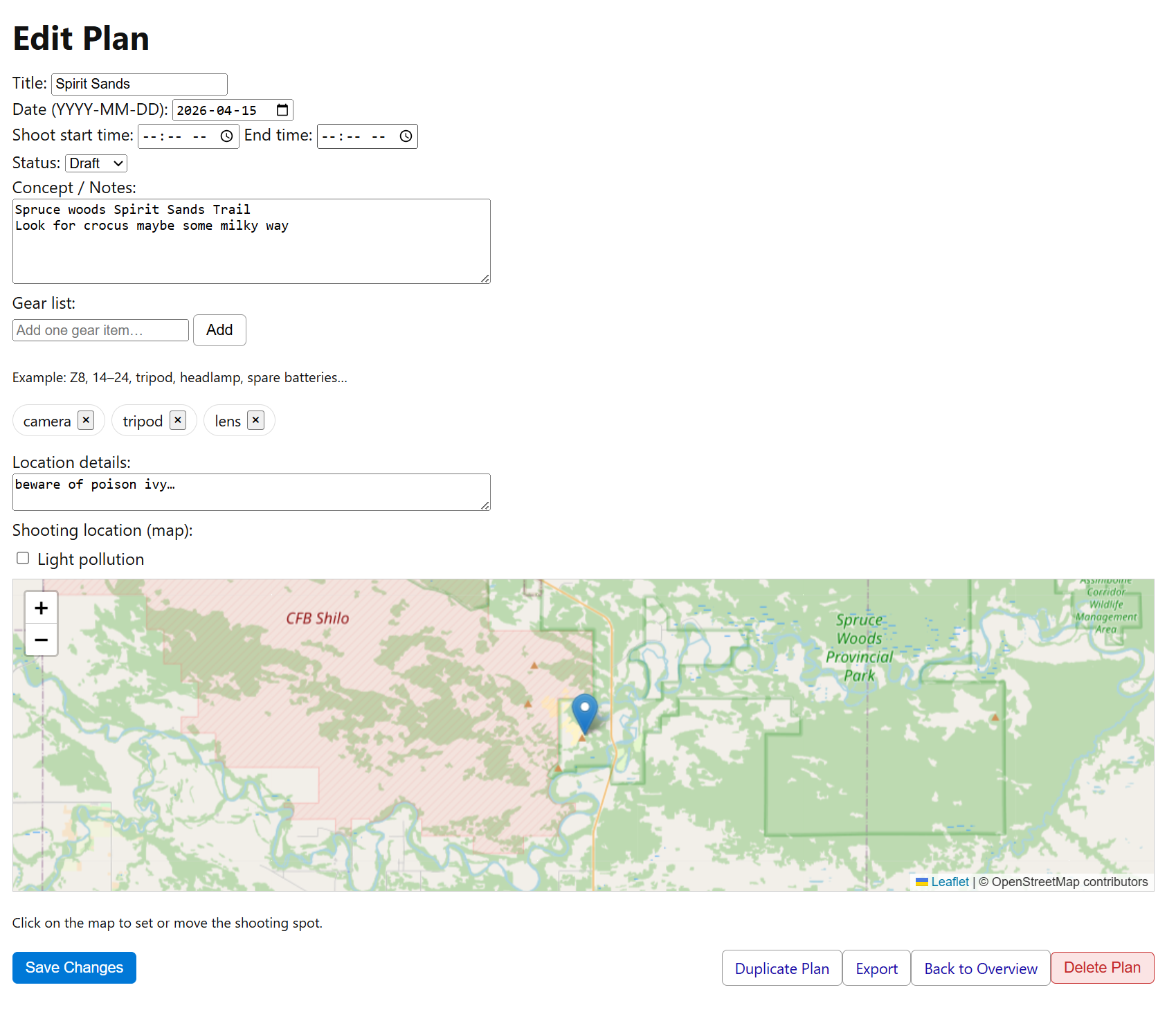

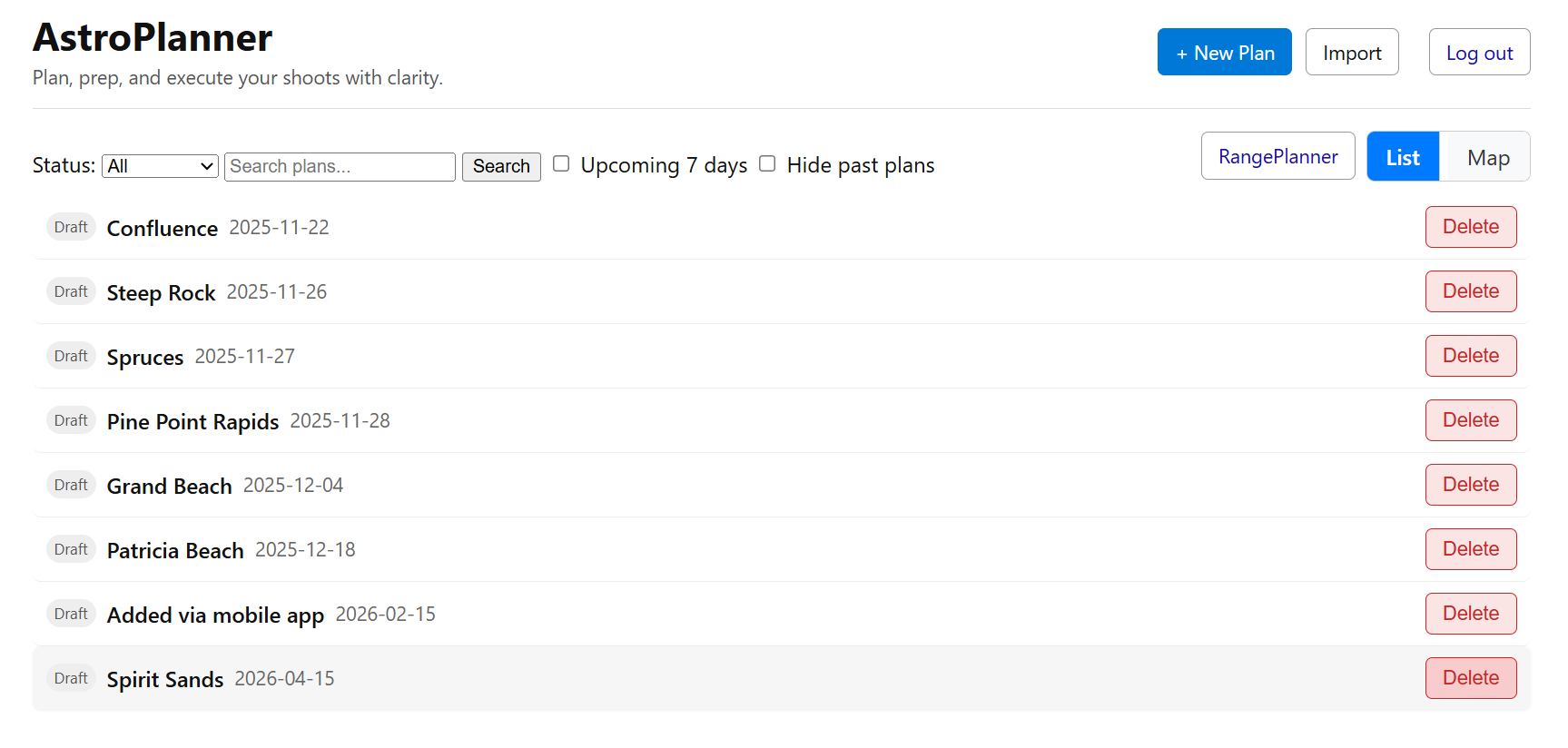

I knew where I needed to go from there. When I started building the web app, it began with the planning tool. It was the simplest tool by far and would be the easiest to get started with. Not only could I record all the key information I needed about making plans, but it was now easy to manage them. From either of two overviews I built, I can easily access any plan, search and filter them, update them, delete them.

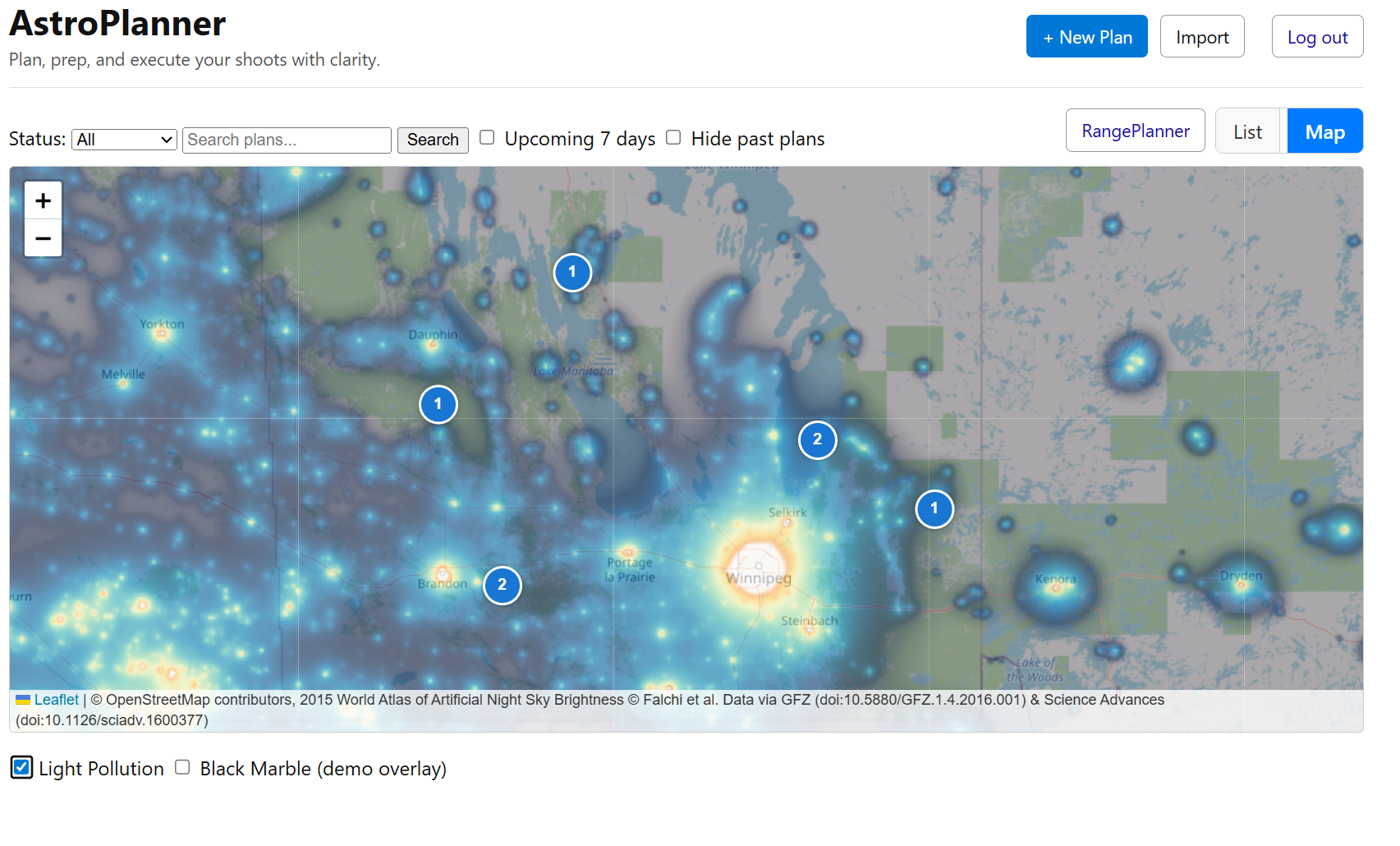

One overview presents all the plans as a list. The other presents them on a map, complete with grouping close proximity plans and a light pollution map for me to see where I have planned photos in relation to where there are dark skies.

List view

Map view with light pollution map toggled on

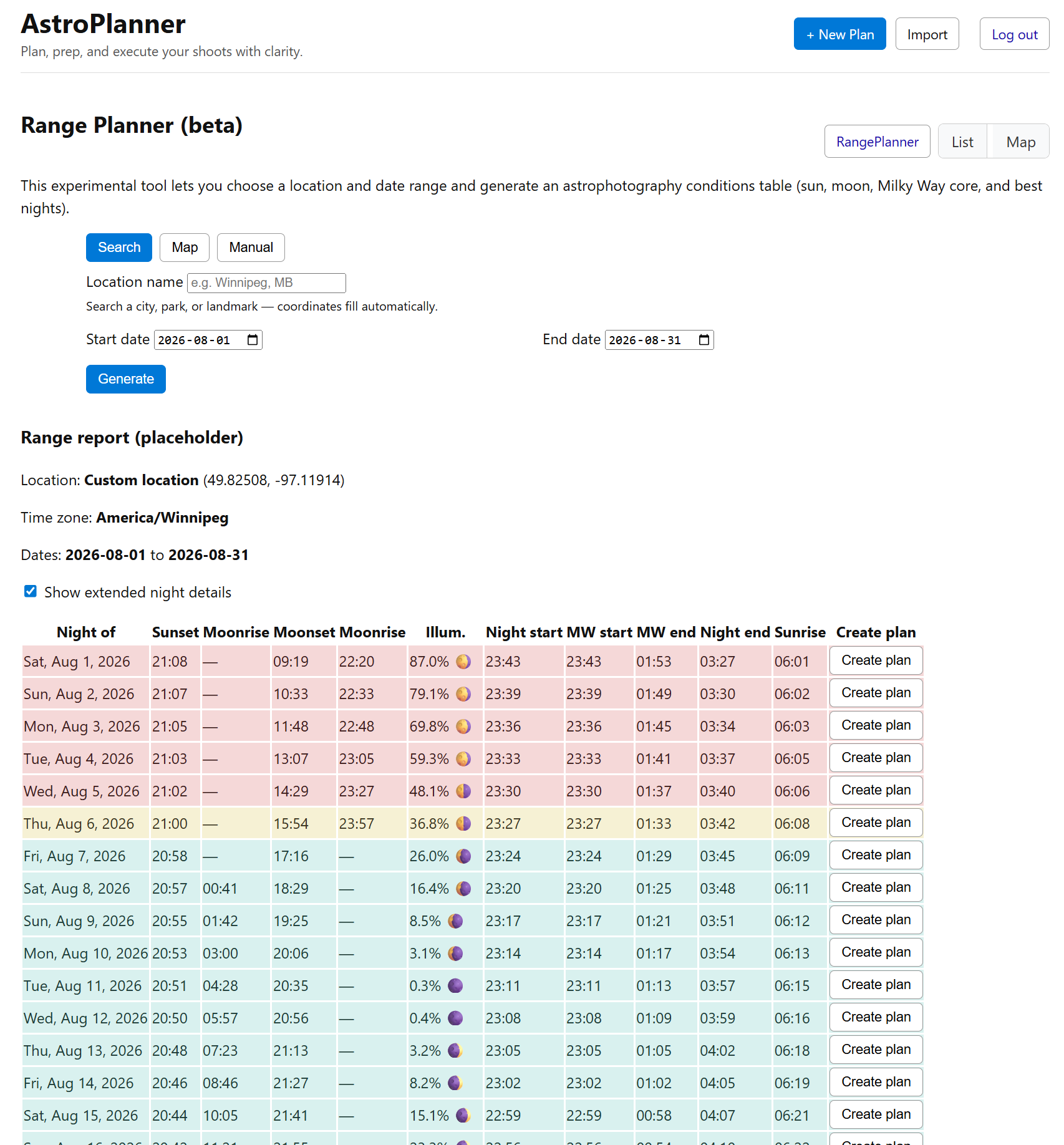

My vision was starting to take shape. It was time to start trying to bring the Astrophotography Dashboard back in. Getting this part right proved to be challenging, but it was important to get it right. While the plans were great for recording ideas, the real power of this app was always going to come from simplifying the research. This planner took several tries to get right. I checked the results against trusted astronomy tools so I know the planner isn’t quietly lying to me — even in weird edge cases like polar night or midnight sun. I can search a location, pick it on a map, or just enter its coordinates. Within seconds, I have all the information I need.

This is how the night sky chart has evolved, though not yet in its final form.

The video below shows the range planner — not because it’s flashy, but because it demonstrates the core idea: quickly seeing which nights are worth caring about without manual cross-checking.

I took the same logic from my first prototype so that I could look at an entire month’s worth of data and know which are the best nights at a glance. I can even choose the one that works best for me and create a new plan directly from the table with location, date, and shooting window pre-filled based on whether I selected Milky Way core, moonrise, or moonset.

For me this project isn’t about building something shiny. It’s about solving a problem I encounter every time I plan a shoot — and about making the process just a bit easier for anyone else who cares about light, timing, and being in the right place at the right moment.

So when I talk about benchmarks or prototypes, what I’m really talking about is:

I want to trust the output, so I can trust my decisions on the ground.

I didn’t set out to build an app.

I set out to make planning night photography less frustrating.

Over the years, planning a single shoot meant jumping between apps, notes, spreadsheets, and gut instinct — and still second-guessing everything once I was standing in the dark. I wanted a way to see the whole picture in one place and trust it.

Nature Photo Planner is my attempt at that. It’s a tool shaped by real nights outside — missed opportunities, close calls, and moments that only happen when timing, light, and preparation line up just right.

It’s still evolving, but this project represents a big shift for me: turning years of experience, trial and error, and problem-solving into something tangible.